RuriDragon, volume 7 by Masaoki Shindo

In return for tutoring, half-dragon Ruri rewards her classmates with knowledge about the draconic world. Terrible, terrible knowledge.

RuriDragon, volume 7 by Masaoki Shindo

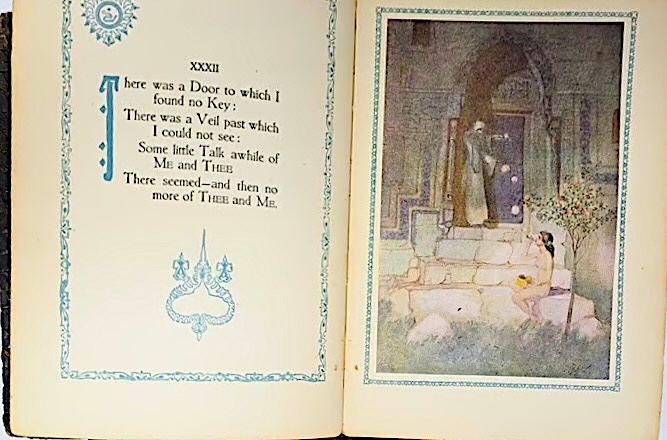

Stanza 32 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám stands as another in a series of existentialist quatrains that stress the inscrutability of death. That is, the poetry questions the meaning of death as a way of questioning the meaning of life.

ΧΧΧΙΙ.

There was a Door to which I found no Key:

There was a Veil past which I could not see:

Some little Talk awhile of Me and Thee

There seemed and then no more of Thee and me.

A. J. Arberry identified the source as no. 403 of the Calcutta manuscript. It is now on the web here.

اسرار اَزَل را نه تو دانی و نه من

وین حرفِ معمّا، نه تو خوانی و نه من

هست از پس پرده گفتوگوی من و تو

چون پرده برافتد، نه تو مانی و نه من

This is my rendering of it as a Fourteener or iambic heptameter:

Not you nor I have known the secrets of eternity.

Not you nor I have solved the riddle that the letter hides.

For there behind the curtain there is talk of you and me,

but when at length the curtain’s drawn, not you remain nor I.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The reference in the second line to the “letter of the riddle” probably concerns the Sufi “science of letters” (`ilm al-huruf), which Gerhard Böwering explained. In part, it sees the Arabic letters as creative and powerful in their own right. Thus the Arabic equivalents of ‘k’ ‘w’ and ‘n’ make up kawn or being. The Qur’an speaks of God creating things out of nothing. He says “Be!” (kun!) and it is. So ‘k’ and ‘n’ are the building blocks of the universe.

As in Hebrew, each Arabic letter has a number equivalent, so one word or phrase can be read as equivalent to another that adds up to the same sum — the science that in Kabbala is called gematria.

Line two of the poem, however, concludes sadly that the unidentified letter in question is a riddle that cannot be solved or “read.”

Illustration by Willy Pogany for a 1909 edition of the Rubáiyát. Public Domain.

Vinnie-Marie D’Ambrosio (Eliot Possessed, New York University Press, 1989, p. 188) saw an echo of this quatrain at the end of modernist poet T. S. Eliot’s 1922 “The Waste Land,” a despairing postmortem on the Lost Generation of WW I and after, referring to FitzGerald’s lines, “There was a Door to which I found no Key:/ There was a Veil past which I could not see.”

Eliot wrote toward the end of The Waste Land :

As in the Rubáiyát, the door does not really have a key, since it is implied that it was locked but could not be reopened, and behind it each person is imprisoned. That key-less door behind which we subsist summed up for Eliot, as it had for FitzGerald, the modern condition of alienation. Yet FitzGerald’s original metaphor simply conveyed the skepticism of the Persian original, the author of which could see no way forward to solving the puzzle of existence and death.

That Eliot had originally wanted to end the poem by quoting the ending of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, where Kurtz says, “The horror, the horror,” suggests that he saw WW I as of a piece with the brutalities of European colonialism (the Belgian Congo was the greatest genocide proportionally of any colonial venture, since it seems to have polished off half the 16 million Congolese). These atrocities at the time marked for him the human condition, or at least signaled the decadence of European civilization. He was at that time deeply depressed and suffering from some sort of recurring neurosis, and was anxious about his mentally fragile wife’s health.

This despair is embedded in a long ending passage drawn from the Hindu work, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Book Five, V.ii. This section is summarized clearly here.

In it, Brahma or Prajapati addresses three orders of beings, the gods, humans and demons. He instructs them to their better natures with the single syllable, “Da!” and they finish his thought. The gods discerned him to mean “damayat” — control or self-discipline. Humans heard “Da!” to imply datta — to be giving and generous. The demons (in Hinduism not necessarily evil but who flirted with the dark side and could give themselves over to greed, lust and other sins) heard “Da!” as a command to engage in compassion or Dayad-hyam.

Eliot prefaced this section of “The Waste Land” with this instruction of “Be Compassionate” in Sanskrit, suggesting that he thought the people of the post-War period were akin to the Hindu demons or asuras — beset by immoderate passions. Certainly, they had polished off some 11 million people with war lust. Likewise, he references Shakespeare’s tragedy about the Roman General Coriolanus, who is exiled, allies with enemies of Rome against his own city, and then is betrayed and killed by his new supposed allies. Coriolanus was in a prison of his own making, of multiple betrayals — just as were the world’s nations after the revelation that there could be a murderous, fruitless World War.

While the Upanishads offered people a way out of their unfortunate condition, Eliot seems not to think that the asuras of 1922 would take the advice to be compassionate but would instead remain locked up behind a door with no key (or with a key that only worked once, to imprison these demons in their passions).

If D’Ambrosio is correct about the reference to the Rubáiyát 1:32 in this passage of “The Wasteland,” it shows the way that Eliot tempered the optimism of the Upanishads with medieval Iranian and Victorian modernist pessimism about the human condition.

—-

For the previous quatrain, see “Through the Seventh Gate:” FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:31.

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

Florence, Italy (Special to Informed Comment; Feature) – The 12-day war of the summer of 2025 ended as abruptly as it began. Israeli aircraft struck targets across Iran, focusing on military infrastructure and sites long associated by Western intelligence agencies with Tehran’s missile and nuclear programs. Iran responded with waves of missiles and drones aimed at Israeli territory and regional targets, briefly pushing the Middle East to the edge of a wider conflagration. Diplomatic channels, activated in parallel with military escalation, eventually produced a cease-fire brokered quietly by outside powers anxious to prevent a regional collapse. The guns fell silent, but few observers believed the conflict had been resolved. Almost from the moment the cease-fire took hold, analysts described it not as peace but as a tactical pause, an intermission before the next act of a war whose underlying drivers remained untouched.

In the months that followed, both sides treated the cease-fire less as an endpoint than as an opportunity. Israel moved quickly to replenish and expand its air-defense systems, accelerating procurement of interceptor missiles and upgrading early-warning and radar capabilities. Iranian officials, for their part, emphasized resilience and recovery, while quietly escalating the production of ballistic missiles and expanding related infrastructure. Western and regional intelligence assessments suggested that Tehran viewed deterrence as its primary shield, betting that a larger and more diversified missile arsenal would complicate any future Israeli or American strike. By early winter, the military balance looked less like a cooling-off period and more like two coiled springs, compressed and waiting.

That sense of impending escalation sharpened this week when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traveled to Florida for an extended meeting with President Donald Trump. According to people briefed on the discussions and media reports citing allied diplomatic sources, the conversation ranged broadly across the Middle East but focused heavily on Iran. Trump, who has positioned himself as a decisive actor on national security, was said to have signaled support for a renewed campaign aimed at Iran’s nuclear facilities and ballistic missile arsenals. While no formal announcement followed the meeting, the language used by aides and allies suggested what one regional diplomat described as a “green light in principle,” contingent on timing and circumstances. For Tehran, the message was unmistakable: the military option is not only back on the table, it may be closer than many expected.

Israel’s calculations are informed not only by military readiness but by political assumptions about Iran’s internal dynamics. Before the summer 2025 strikes, Israeli intelligence assessments reportedly concluded that sustained external pressure might fracture Iranian society and weaken the Islamic Republic from within. The expectation was that economic hardship, social discontent and political fatigue would combine with military shocks to produce mass unrest, perhaps even a challenge to the regime’s survival. Instead, the attacks had the opposite effect. The strikes triggered a classic rally-around-the-flag response, uniting broad segments of Iranian society across ideological and class lines against what was widely perceived as foreign aggression. Public dissent did not disappear, but it was temporarily subsumed by a surge of nationalist solidarity.

Today, that unity shows visible cracks. Iran’s economy has deteriorated sharply since the war, battered by sanctions, capital flight and structural mismanagement. Inflation has surged to levels that economists inside and outside the country describe as destabilizing, eroding purchasing power and hollowing out the middle class. The national currency has lost a significant portion of its value, pushing basic goods out of reach for many households and squeezing businesses already operating on thin margins. In recent weeks, protests have spread in major cities, led largely by merchants, small business owners and salaried workers who once formed a relatively stable economic base.

At the center of the unrest is a widening gap between wages and prices. The government has proposed increasing salaries by roughly 20 percent for the coming year, even as independent estimates place inflation above 50 percent. For many Iranians, this is not a policy debate but a mathematical impossibility: incomes are rising far more slowly than the cost of living, guaranteeing a further decline in real wages. Labor unions, professional associations and informal business networks have voiced growing frustration, warning that incremental adjustments will not avert a deeper crisis.

The fiscal picture is equally bleak. Iran’s new financial year begins on March 20, yet the government has struggled to finalize a workable budget. Officials privately acknowledge a significant deficit. The overall budget is estimated at around $100 billion, but oil exports,long the backbone of state revenue, are expected to cover only about 40 percent of that total under current conditions. The remainder would need to be raised through aggressive and largely unprecedented taxation schemes, targeting sectors that are already under pressure. Economists warn that such measures risk accelerating capital flight and deepening public anger, further eroding the regime’s legitimacy.

From Jerusalem, these developments are being watched closely. Israeli strategists have long debated whether external military pressure combined with internal economic stress could produce a different outcome than the one seen last summer. This time, some argue, the social contract in Iran appears more fragile. Protests driven by inflation and fiscal chaos lack the nationalist cohesion that followed direct military attacks. For hardliners in Israel, this moment presents an opportunity: a weakened adversary, distracted by domestic turmoil, may be less capable of sustaining a prolonged confrontation.

Photo of Kaveh Blvd., Tehran, Iran by Roozbeh Eslami on Unsplash

The risks of such reasoning are substantial. History offers ample evidence that external attacks can once again consolidate internal support, even in societies riven by economic hardship. A renewed Israeli campaign aimed not only at degrading missile and nuclear capabilities but at forcing regime change would almost certainly provoke a fierce response, drawing in regional proxies and potentially the United States. Energy markets, already sensitive to geopolitical shocks, would react sharply, and civilian populations on all sides would bear the costs.

Whether war begins in the next hours or unfolds after months of maneuvering, the trajectory is increasingly clear. Diplomatic off-ramps appear narrow, domestic pressures inside Iran are intensifying, and regional actors are preparing for scenarios they publicly deny seeking. Another conflict is not inevitable, but it is no longer abstract. It is being planned, debated and budgeted for, even as ordinary people from Tel Aviv to Tehran brace for the consequences. The pause that followed the 12-day war is ending, and the shadow of another, potentially bloodier confrontation is lengthening across the region.

By

( Foreign Policy in Focus ) – The United States is drawn to war on every front, like a moth to a candle. It does not matter that Americans are sick of foreign wars stretching back 25 years in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and now Venezuela, wars that have bankrupted the nation. It has no effect that the United States lacks the economic, technological, and manufacturing capacity necessary to sustain a conventional war. Nor would the United States likely win an unconventional war employing nano-technology, bio-technology, and information warfare.

The critics allowed to appear on TV like John Mearsheimer and Jeffrey Sachs attribute this war-mongering to the foolishness and the ignorance of political leaders like Donald Trump, or to the incompetence of bureaucrats. They intentionally avoid any analysis of the economic structure of the United States, or the role of multinational banks and corporations in the formulation of policy. Their only explanation for the drive for war is the foolish actions of a “few bad apples.”

No one wants war, including the rich and powerful on all sides, in Beijing and Washington, in Berlin and Moscow, in Tehran and Tel Aviv. Yet the beating of the drums of war continues, and it grows louder. The appetite for war spreads like a vermillion fungus across the entire nation, with a military culture pushed through newspapers, movies, and television broadcasts. Preparation for war is a means of controlling the “little people” in a totalitarian manner.

The U.S. government is pressuring every ally to rapidly increase defense spending, up to five percent, and to do so far more rapidly than can possibly be done in such a short time without massive corruption and waste. The military buildup is but a transfer of wealth, not an increase in security.

The United States is collapsing as an economy, as a society, and as a civilization, weighed down by a massive debt, burdened by collapsing infrastructure and dying educational and research institutions, and strangled by a culture of pornography and narcissism. Above all, the extreme concentration of wealth over the last 20 years, since government was captured completely by the super-rich, has meant that a handful of conceited frauds can determine the policy for the entire nation, and decide the fate of everyone. The basic interests of the vast majority of citizens are entirely ignored. The republic, and all traces of participatory democracy, have been consigned to the trash bin of history.

The international trade system and the embrace of “free trade” ideology played a major role in pushing the United States toward war around the world. Supply chains link together factories in loops that encircle the globe. Manufactured goods and agricultural products are brought into the United States from over the world, not because doing so is good for Americans, but because the multinational banks that control the economy seek out the cheapest labor and cheapest goods. Virtually all consumer goods in the United States go through logistics and distribution systems controlled by multinational corporations. Unlike the situation in 1945, a large part of the money that citizens (rebranded as “consumers”) spend at Walmart, Best Buy, or Amazon goes to the stockholders of those corporations and offers little or no benefit for the local economy.

Until the 1950s, most of what Americans ate came from local, family-owned farm. Clothes and furniture were also produced locally. Now that production and distribution have been spread all over the globe, events far away directly impact the U.S. economy, and sometimes politicians feel pressure to use military threats, or responses, to protect American corporate interests (repackaged as “national security”).

So, too, U.S. dependency on petroleum did not exist in the 1920 or dependency on rare earth metals in the 1980s. These are problems created by the decisions of corporations to introduce technologies that offered some conveniences, but at the price of extreme dependency of citizens on technology, which has generated large corporate profits.

The relocation of American manufacturing overseas also means that the only employment available in many regions, especially rural areas, is as police officers, guards at prisons, soldiers, or other positions in the military, police, or surveillance system. These days, security and the military are the only parts of the government budget that are growing.

The last decade has seen employment in defense surge by 40 percent, reaching 1.4 percent of the total employment base. In 2022-2023 alone the workforce expanded by 4.8 percent in contrast to an average of 1.7 percent.

No politician can oppose the increase in the military budget because, although constant foreign wars do great damage to the economy as a whole, the military has become the only part of government that increases opportunities for employment locally.

The U.S. economy is increasingly controlled by a small number of rich families. The wages of American workers have been reduced and the costs of living greatly increased for the profit of the few. The unprecedented concentration of wealth in the hands of a group of oligarchs has changed everything. This restructuring of society may not seem to be military in nature, but it pushes the United States toward a military economy.

The disposable income of workers increased beginning in the 1940s because of the redistribution of wealth forced by the reforms of the New Deal. These reforms also allowed for corporations to make enormous profits after the 1950s by selling consumer products to working people who had the disposable income to purchase them. From the 1960s on, consumption, growth, and the stock market became the primary tools for assessing the health of the economy.

Particularly from the 1970s on, this system effectively funneled wealth from working people to the wealthiest. But today consumption by workers, the middle class, and even the upper middle class is no longer sufficient to generate profits for corporations because the people cannot spend any more. Banks have been forced to look for some other source of profit to pay off their debts. One direction they looked has been the military. Military spending creates steady demand that is not tied to market conditions, or economic booms and busts. It is funded by the people through taxes, or through the inflation created by the deficit spending that funds military expenditures.

The increase in military spending is a policy choice; it is the only way to avoid economic collapse. It must be justified by threats from China, Russia, and Iran, or terrorism. Intelligence agencies responding to the demands of banks to do everything they can to create trouble with those countries.

Companies like Oracle, Palantir, Google, and Amazon not only grow fat like ticks feeding on the military and intelligence budgets, they are merging with banks and using their control of the IT systems that power banks as a means to seize control of money itself through digitalization of the dollar, or the introduction of cryptocurrencies.

One of the most powerful billionaires, Larry Ellison, has launched a campaign to dominate media through the control of social media, entertainment and news broadcasting. The Trump administration forced TikTok’s Chinese owner ByteDance to turn over its operations in the United States to a consortium headed by Ellison’s company Oracle in December 2025. Oracle grew to global influence as a major contractor for the CIA, and Ellison is a strong Trump supporter.

Since Ellison’s son David was installed as CEO in August 2025 of the new entertainment conglomerate Paramount Skydance—the merger of Paramount Global, Skydance Media and National Amusements—father and son have been raising enormous funds for a hostile takeover of Warner Brothers that would give them unprecedented control over entertainment and journalism in the United States. Already CBS, under Ellison rule, has cancelled at the last minute a 60 Minutes report on the notorious El Salvadorian prison CECOT.

These IT firms made those billions by taking out massive loans that they then used to buy back their own stock. They have nothing but debt and money in digital form. War, the threat of war, the build-up for war, is what keeps them going.

The United States government is a republic consisting of three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. The three branches complement each other, and they also regulate and balance out each other. This system ensures that power is not concentrated in any one place.

That was a long time ago. How does politics really work today?

There are three real branches of government today, and they are quite different than those described in the Constitution. The true three branches of government are the politicians, the bankers, and the generals. They are the ultimate powers behind the government, and they balance each other out because they operate at different levels and have different strengths.

The politicians are able to form temporary alliances among interest groups in business, finance, and government and negotiate among them to determine policy. The bankers control money and have the power of financial manipulation to shut down the entire economy, or the activities of opponents. The generals possess a chain of command that cannot be easily broken by exterior forces, even by money, and they have the ability to use force directly, without relying on a third party, to achieve their goals.

In a healthy society, where citizens actually play a role in politics, the politicians rise to the top because their primary mission is serving the needs of their clients, whether they are bankers, businessmen, generals, or other interest groups in the general population. Politicians can play the central role because they reflect the needs of citizens. As long as politicians can effectively meet the needs of the bankers, the generals, and the citizens, and keep the money flowing to them, the system remains stable.

If wealth is too concentrated, however, to the degree that the bankers can pay off everyone and gain complete control of the economy, then they rise to the top because bankers need only service a small number of the super-rich to obtain absolute power. The politicians become their puppets and the generals are paid off by the bankers. That is what the political system in the United States has become today.

A political system run by bankers, however, will encounter enormous problems over time because everything will be decided on the basis of short-term profits, and no one will do anything for the sake of others, or follow an ideal greater than personal interest. As a result, the foundations of government, and of society, will crumble. Eventually the government will collapse into anarchy, or it will drift into war as a means of generating profits and enforcing the bankers’ iron-fisted rule over the people.

At that historical moment, the generals rise to the top because they have a viable chain of command that continues to function even as the government fails, and because they speak the language of force and violence, which will become the only language that has authority once the legitimacy of politicians and bankers has been destroyed.

The concentration of wealth has almost eliminated the impact of citizens on policy. The finance-driven speculative economy has brought trust in government and business to a new low. As a result, the only politicians in the Democratic Party who are able to take on the Trump administration are all former military and intelligence, and the election of a former CIA officer Abigail Spanberger as governor of Virginia suggests that the “CIA Democrats” have become the driving force in an ideologically bankrupt Democratic Party.

The financial kings, the bankers and billionaires, need make only one little mistake in order for the chain of command to be handed over to the military in the United States. Although military officers may not want war as individuals, once the order goes down, the entire process, especially in light of the massive increase in drones and robots in the military, will be literally on automatic.

By Morteza Hajizadeh, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

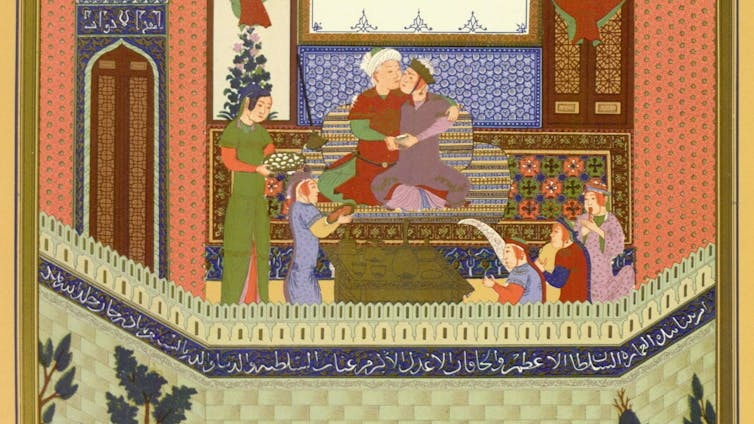

(The Conversation) – For centuries, literature from Islamic regions, especially Iran, celebrated male homoerotic love as a symbol of beauty, mysticism and spiritual longing. These attitudes were particularly pronounced during the Islamic Golden Age, from the mid-8th to mid-13th centuries.

But this literary tradition gradually disappeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, under the influence of Western values and colonisation.

Attitudes towards homosexuality in early Islamic societies were complex. From a theological perspective, homosexuality started to become frowned upon from the 7th century, when the Quran was said to have been revealed to the Islamic Prophet Mohammad.

However, varying religious attitudes and interpretations allowed for discretion. Upper-class medieval Islamic societies often accepted or tolerated homosexual relationships. Classical literature from Egypt, Turkey, Iran and Syria suggests any prohibition of homosexuality was often treated with leniency.

Even in cases where Islamic law condemned homosexuality, jurists permitted poetic expressions of male–male love, emphasising the fictional nature of verse. Composing homoerotic poetry allowed the literary imagination to flourish within moral boundaries.

The classic Arabic, Turkish and Persian literature of the time featured homoerotic poetry portraying sensual love between males. This tradition was sustained by poets such as the Arab Abu Nuwas, the Persian masters Saadi, Hafiz and Rumi, and the Turkish poets Bâkî and Nedîm – all celebrating the beauty and allure of male beloveds.

In Persian poetry, masculine pronouns could be used to describe both male and female beloveds. This linguistic ambiguity that further legitimised literary homoeroticism.

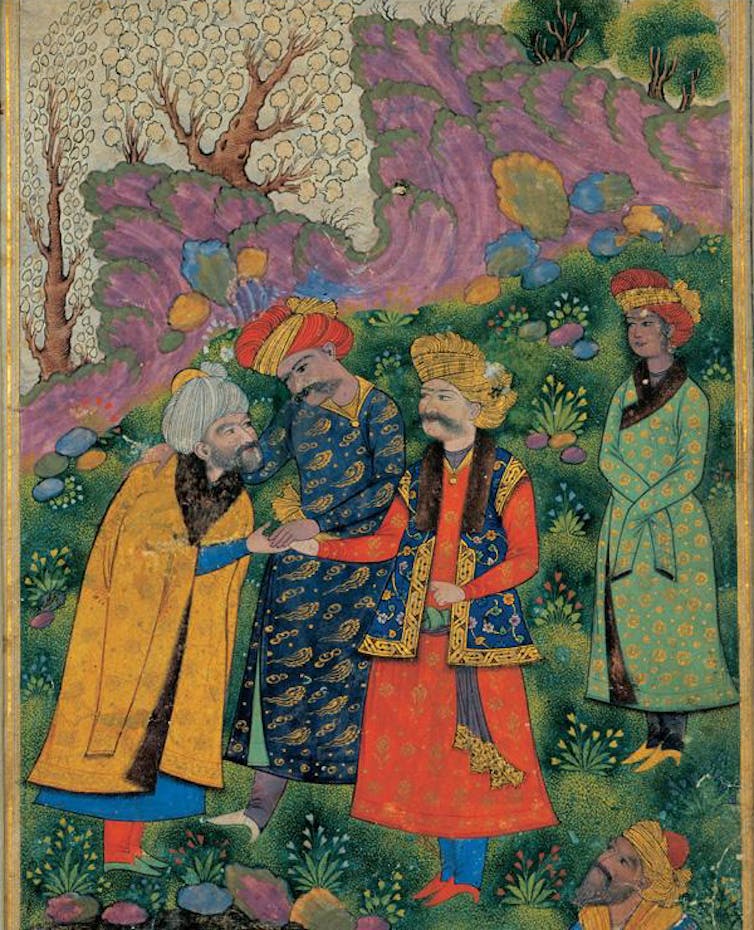

In Sufism – a form of mystical Islamic belief and practice that emerged during the Islamic Golden Age – themes of male–male love were often used as a symbol of spiritual transformation. As professor of history and religious studies Shahzad Bashir shows, Sufi narratives frame the male body as the primary conduit of divine beauty.

Religious authority in Sufism is transmitted through physical closeness between a spiritual guide, or sheikh (Pir Murshid), and his disciple (Murid).

The sheikh/disciple relationship enacted the lover–beloved paradigm fundamental to Sufi pedagogy, wherein disciples approached their guides with the same longing, surrender and ecstatic vulnerability found in Persian love poetry.

Literature suggests Sufi communities developed around a form of homoerotic affection, using beauty and desire as metaphors for accessing the hidden reality.

Thus, the saintly master became a mirror of divine radiance, and the disciple’s yearning signified the soul’s ascent. In this framework, embodied male love became a vehicle for spiritual annihilation and rebirth within the Sufi path.

The legendary love between Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni and his male slave Ayaz exemplifies this. Overwhelmed by seeing the beauty of a naked Ayaz in a bath, Sultan Mahmud confesses:

When I saw only your face, I knew nothing of your limbs. Now I see them all, and my soul burns with a hundred fires. I do not know which limb to love more.

In other stories, Ayaz willingly offers himself to die at Mahmud’s hands. This symbolises spiritual transformation through the annihilation of the ego.

The relationship between Rumi and Shams Tabrizi, both 13th-century Persian Sufis, is another example of male–male mystical love.

In one account from their disciples, the pair reunited after a long period of spiritual transformation, embraced each other, and then fell at each other’s feet.

Rumi’s poetry blurs spiritual devotion and erotic attraction, while Shams challenges the idea of idealised purity:

Why look at the reflection of the moon in a bowl of water, when you can look at the thing itself in the sky?

Homoerotic themes were so common in classical Persian poetry that Iranian critics claimed

Persian lyrical literature is essentially a homosexual literature.

By the late 19th century, writing poetry about male beauty and desire became taboo, not so much on religious injunctions, but because of Western influences.

British and French colonial powers imported a Victorian morality, heteronormativity and anti-sodomy laws to countries such as Iran, Turkey and Egypt. Under their influence, homoerotic traditions in Persian literature were stigmatised.

Colonialism amplified this shift, framing homoeroticism as “unnatural”. This was further reinforced by the strict administration of Islamic laws, as well as nationalist and moralist agendas.

Influential publications such as Molla Nasreddin (published from 1906 to 1933) introduced Western norms and mocked same-sex desire, conflating it with paedophilia.

Library of Congress, CC BY-SA

Iranian nationalist modernisers spearheaded campaigns to purge homoerotic texts, framing them as relics of a “pre-modern” past. Even classical poets such as Saadi and Hafez were reframed or censored in Iranian literary histories from 1935 onward.

A millennium of poetic libertinism gave way to silence, and censorship erased male love from literary memory.![]()

Morteza Hajizadeh, Hajizadeh, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Remember that serious back spasm I had around three weeks ago? Things haven’t really gotten better. In fact, I’m having random shooting pain in my sides, hips, and down my thighs. So for once in my life I’m doing the sensible thing and have canceled my trip to Arizona for the week-long company kickoff. Airline travel + wrangling luggage + hotel bed is a perfect combo to cause even worse spasms, and I don’t want to run the risk of having to go to the hospital while I’m away.

I am, of course, feeling MASSIVE guilt about this. Even tho’ I know my new boss and team will support my doing this. This decision is also triggering my ever-present imposter syndrome about I don’t really know how to approach things for my new position and that all of this will lead to me being fired. Logically I know that’s not the case, but whoo the Brain Raccoons are loud

🎁 Programming note: A quick update on what to expect from WTFJHT as we head into the holidays... I’ll be publishing Monday, Dec. 29 and Tuesday, Dec. 30, before returning to my regular Monday–Thursday schedule on Monday, Jan. 5, 2026. As always, if something truly WTF-y happens, I’ll be here. Otherwise, this is a short pause to recharge and spend some time with family. Thanks for reading, sharing, and supporting this project. It means a lot and I’m glad you’re here. -MATT

Send your thoughts, suggestions, or complaints to:

matt@whatthefuckjusthappenedtoday.com

Today in one sentence: A federal judge ordered the Trump administration to continue funding the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; a federal judge ruled that the Trump administration can share limited Medicaid data with ICE; the U.S. imposed sanctions on 10 people and companies in Iran and Venezuela, claiming they were involved in drone and missile-related weapons trade between the two governments; Trump threatened to "probably bring a lawsuit against" Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell for “gross incompetence"; Trump told his supporters that Democrats would “steal” their “tariff rebate checks” unless they send him money within an hour; nearly one in four U.S. workers were “functionally unemployed” in November; and at least three artists canceled performances at the Kennedy Center after Trump’s name was added to the building.

1/ A federal judge ordered the Trump administration to continue funding the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, rejecting the claim that the law prevents the agency from receiving money from the Federal Reserve. U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson said the administration violated an existing court order by refusing to request funding it’s legally permitted to seek. She said the refusal was used to bring the agency’s operations to a halt, calling the rationale “an unsupported and transparent attempt” to evade the injunction. The ruling came as the CFPB warned it could run out of money in early 2026. Jackson wrote that neither the funding statute nor the Fed’s willingness to provide money had changed, only the administration’s determination to eliminate an agency created by Congress. (CNN / New York Times / NPR / Politico / CNBC)

2/ A federal judge ruled that the Trump administration can share limited Medicaid data with ICE, but questioned the clarity and scope of the policy behind the data use. U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria said HHS and the Department of Homeland Security may share basic biographical, contact, and location information about immigrants living in the U.S. unlawfully, writing that the sharing of such data “is clearly authorized by law.” At the same time, he blocked broader data transfers, finding that ICE’s policies for requesting additional information are “totally unclear and do not appear to be the product of a coherent decisionmaking process.” The decision partially lifts an earlier injunction while keeping limits on how sensitive Medicaid data can be used while the case continues. (Axios / Politico / The Hill)

3/ The U.S. imposed sanctions on 10 people and companies in Iran and Venezuela, claiming they were involved in drone and missile-related weapons trade between the two governments. The Treasury Department said the targets include a Venezuelan aerospace firm accused of purchasing Iranian drones and several Iran-based individuals and companies linked to efforts to obtain chemicals used in ballistic missiles. The sanctions followed warnings from Trump that the U.S. would “knock the hell” out of Iran if it rebuilds its missile or nuclear programs. (Associated Press / Bloomberg / CNBC)

4/ Trump threatened to “probably bring a lawsuit against” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell for “gross incompetence,” claiming “the guy is just incompetent.” Trump didn’t identify a legal claim or evidence for a case against the head of the independent central bank, but Trump administration officials have claimed Powell lied to Congress or mismanaged the Fed’s multibillion-dollar building renovation. The Fed has said pandemic-era disruptions drove up costs. Powell’s term as chair ends in May 2026. (Washington Post / New York Times / Axios / Wall Street Journal / Business Insider / Bloomberg / CNBC)

5/ Trump told his supporters that Democrats would “steal” their “tariff rebate checks” unless they send him money within an hour. In a fundraising email, Trump urged donors to “STOP THE BOIL NOW BEFORE MY END-OF-YEAR FUNDRAISING DEADLINE,” claimed that “Dems want to send your check to illegals,” warned “WE’RE WALKING ON RAZOR-THIN ICE!” and insisted that “MAGA can’t afford to wait any longer” or “EVERYTHING we’ve worked so hard to accomplish could go BYE BYE.” The email promoted a non-existent $2,000 “rebate check” program. (New Republic / Daily Beast / Alternet)

6/ Nearly one in four U.S. workers were “functionally unemployed” in November. The Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity said 24.8% of workers were either jobless, unable to find full-time work, or earning $26,000 a year or less, compared with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 4.6% unemployment rate. LISEP Chair Gene Ludwig said standard measures miss whether jobs actually support basic living needs, arguing they are “deceiving” because they exclude underemployment and poverty wages. (Newsweek / Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity)

7/ At least three artists canceled performances at the Kennedy Center after Trump’s name was added to the building. Jazz supergroup the Cookers withdrew from a scheduled New Year’s Eve concert, folk singer Kristy Lee canceled a mid-January show, and Doug Varone and Dancers pulled out of two April performances. Cookers saxophonist Billy Harper said he would not perform in a venue he said represents “overt racism and deliberate destruction of African American music and culture.” The latest withdrawals follow earlier cancellations by Issa Rae, the producers of “Hamilton,” and jazz musician Chuck Redd after Trump removed the board, installed allies, and approved the renaming. Kennedy Center President Richard Grenell said shows artists were “unwilling to perform for everyone — even those they disagree with politically.” (New York Times / NBC News / Washington Post / Associated Press)

⏭️ Notably Next: The 2026 midterms are in 308 days.

Support today’s essential newsletter and resist the daily shock and awe: Become a member

Subscribe: Get the Daily Update in your inbox for free

Top Secret! (the exclamation point is part of the title) makes not one single solitary goddamned bit of sense. It’s a movie from the 80s with a hero from the 50s in a geopolitical setting from the 60s featuring stock characters from the 40s, starring an actor whose biggest hits would happen in the 90s. Confused yet? Welcome. Sit down, we have a story to tell.

And that is that Top Secret! is not really the story of whatever the hell the story of Top Secret! is, it’s the story of three filmmakers — Jim Abrahams, David Zucker and Jerry Zucker, known collectively as “ZAZ” — who had a phenomenal success with a movie and now had to follow it up with more of the same. The phenomenal hit was Airplane! (yes, that exclamation point is a running gag), the 1980 spoof that was made for $3.5 million and raked in $83 million at the box office, becoming the fourth highest-grossing film of the year. It’s the sort of smash hit you dream about making, until the movie studio comes back to you and says, basically, “do it exactly the same, but different.”

This is hard to do! Especially when the movie in question is Airplane!, which was less a movie than it is a non-stop automated buffet of slapstick, sight gags and absurdist dialogue, sending up disaster films, one of the most reliable genres of spectacle in the 70s, and the very successful Airport series of films in particular (also a 1957 movie called Zero Hour, whose plot ZAZ borrowed from so liberally that they ended up having to get the rights for it, which technically makes Airplane! a remake). Audiences of 1980 understood the scaffolding on which all the jokes for Airplane! were hung. They were all the hits they’d seen in the theaters and drive-throughs in the years right before this one.

When it was time for a sequel, the obvious thing to do was just to make Airplane! Two!, but ZAZ chose to zig instead of zag (there was an Airplane 2: The Sequel in 1982, which ZAZ had nothing to do with; it was written and directed by a Ken Finkelstein, who would that same year write Grease 2, and what can one say about that, except, that’s an interesting filmography you got there, Mr. Finkelstein). First ZAZ made Police Squad! for TV, which lasted six episodes, and then they made Top Secret!, with the mishmash of plots and influences mentioned above.

Top Secret! didn’t exactly flop. But after raking in just $20 million in box office off a $9 million budget, it wasn’t the smash hit Airplane! was, either (Box Office Mojo has it coming in as the 43rd most successful movie of 1984, below Never Cry Wolf, but above Hot Dog… the Movie, which for the avoidance of doubt was a movie about skiing, not tubes of processed meat). What happened? My best guess is that Airplane! was parodying one thing, disaster movies, which the audience knew about. Top Secret! parodied many things, none of which the audience cared about, and then mashed them all together, making them make even less sense. Jokes are jokes but if you want to sell them in the world of 1984, you had do a little more work, apparently.

Don’t feel too bad for ZAZ. They got their mojo back in 1986 with Ruthless People, and in 1988 with The Naked Gun (written by ZAZ, directed by just one Z), which unlike Top Secret! was parodying just one thing again. Then in 1990 Jerry Zucker, by himself, had the number one box office hit of the year with Ghost. They did fine. But it does leave Top Secret! as the odd man out in their filmography. Heck, even 1977’s The Kentucky Fried Movie, which ZAZ wrote with John Landis directing, was more successful as a matter of return on investment.

It’s a shame because Top Secret! is hilarious, and in the fullness of time, in which all the cinematic antecedents of this film sort of blur into mush and don’t really matter anymore — just as they’ve done with Airplane! and The Naked Gun — the ridiculous rat-at-tat of the jokes in this film are the thing that remain and shine. They’re just as good as the ones you get in those other films (with the admission that “good” is not precisely the word for these jokes), and in some cases they might even be better.

And none of ZAZ’s other films has this film’s secret weapon, which is Val Kilmer, in his big screen debut. Kilmer plays the pop star Nick Rivers, who is so clearly based on 50s Elvis that Kilmer showed up for his audition as Elvis, or at least an Elvis impersonator, with an Elvis song prepared (and yet Nick Rivers’ “big hit” is a Beach Boys pastiche, so… go figure). Kilmer was unquestionably one of the prettiest humans on the planet when he made this movie (prettier even than his costar Lucy Gutteridge, who was plenty pretty by actual mortal human standards), and he even sings all the Nick Rivers songs in the movie. If ever there was someone meant to play a 50s rock star in the 80s going to visit an East Germany stuck in the 60s with French rebels from the 40s, it was Kilmer.

The ZAZ team have commented that the Julliard-trained Kilmer sometimes had problems understanding his character, but it doesn’t show in the final product. Also, really now, what’s there to understand? Stand there and look pretty, Val! Sing a song! Play your lines like you’re in an actual movie, not a parody! This ain’t rocket science! It is submarine science, since there’s a plot point (such as it is) that a kidnapped scientist is trying to develop mines to destroy NATO’s submarine capabilities, but never mind that now! Anyway, Kilmer is perfect in this role. I understand that it was his role as Iceman in Top Gun that launched ten million confused sexualities, but just know some of us got there early with this one. Yes, I admit it, my sexuality is “Straight with a carve-out for Nick Rivers.” Now you know.

Don’t worry about the plot. For God’s sake, don’t worry about the plot. This is one movie that is improved, in the matter of story, by having slept through any class you might have ever taken on 20th Century European history. No one under the age of 36 was even alive for the fall of the Berlin Wall; the idea of the East Germans anachronistically wearing WWII-era German uniforms will make even less sense to them than it did at the time for those of us now in the full bloom of middle age. What is the French resistance doing in East Germany? Don’t ask. Did East Germany have Bavarian-decorated malt shops where the kids wore poodle skirts? I said, don’t ask. And how does an underwater Western saloon fit into all of this? Listen, kid. I keep telling you.

I do wonder how this movie would play for anyone not alive or cognizant in the 80s, much less the several other decades referenced in this film. My feeling is that it would play well, for the reason I mention above, that the fullness of time has rendered its provenance mostly irrelevant, so the silly jokes are what last. Sure, the jokes about LeRoy Nieman paintings and the Carter Administration won’t play the same way, but there’s another joke coming up 30 seconds later anyway, it’s fine.

That said, I can’t know, short of sitting a millennial or Gen Z person down and making them watch the film. It’s possible they might just watch it and go, wow, that was certainly a thing that happened. But maybe they’ll just go with it and enjoy Top Secret! anyway. They could take comfort in knowing they wouldn’t be the first.

— JS

When 2023 became 2024, I was in the middle of a profoundly painful season of change. It was awful—but at no point was I alone in it. This was by design. My friends and loved ones showed up to surround me with support and care when I needed it most. At the time, only some of those loved ones knew that they were saving my life.

Grief requires tremendous endurance. In those months, I was deeply uncertain about my ability to carry the grief I’d been handed. It was far too tempting to simply set it down. The problem is that grief cannot be separated from the larger project of being alive. The only way to put down one is to give up the other.

But I didn’t have to carry the grief alone. Because of the help I received from my community, I managed to transport my burden across those months, and I came out on the other side of the calendar alive.

I can tell you precisely where I was when I realized everything was different for me. A friend of mine—a very dear sibling of my soul—took a little road trip with me up the California coast. We were on the way to meet up with some pals, and we took an RV through some of the most beautiful places on earth, and we stopped to eat oysters over the bay. With the wind in my face and hot butter on my tongue, I turned to her and said “I love being alive.”

She stared at me for a moment before telling me she couldn’t remember the last time she’d heard me say that. The wild thing was, I meant it. I’d made it through the grief, and I’d found a new version of myself—one that truly, actually wanted to be alive on purpose.

We cried and we laughed and we marveled at the way a few months of terrible pain can lead to a brand new kind of life. As we walked back to our RV I said: This moment of looking out at the water and thinking I want to live doesn’t belong to me. Other people have had this experience. What has it been like for them? I want to know.

The oysters we ate that day had come with a side of garlic fries in a compostable takeout container. I wrote a list of names on the lid of that container. As we started to drive, I said to my friend: I’m going to call it Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive.

Over the next couple of months, I sat down with one of the greatest artists and community organizers in the game, Shing Yin Khor, and got advice on how to launch and fulfill a physical magazine. I solicited cover art from Shing, as well as from Lucy Bellwood, Liana Kangas, and Trung Le Nguyen. I contacted the absolutely genius Kate Burgener to handle the layouts and design of the magazine. I ran a Kickstarter campaign that was quickly and enthusiastically backed by so many of you it made my head spin. I set about making plans with production assistant Josh Storey and copyeditor Lydia Rogue, who carried this project on their backs.

And I dug deep to find the mettle to reach out to everyone whose name I’d written on that box of garlic fries. I am incredibly shy, and reaching out to ask people to write essays or be interviewed for Stone Soup is always very scary. But I steeled myself, and I sent the emails and made the phone calls. I found the courage to ask people to tell me about the lives they've lived, and the things that have made them pursue this enormous project of being alive.

Imagine my shock and good fortune when they said yes.

There were some who wrote about the power of enduring connection. Helena Fitzgerald wrote about being in the next room while the party downstairs continues, and what it means to allow what we love to exist without us. Shing Yin Khor wrote about how little guys connect us across time and space through art. Hailey Piper wrote about fixing things at home and being united with others who have made the same repairs over and over.

Others explored the physical experiences of being alive – odes to embodiment. Chuck Tingle wrote about bath bombs and the ritual of rest. Suyi Davies Okungbowa wrote about the sound of a soccer ball being kicked. Eden Royce wrote about papershell pecans.

Some wrote about the wounds they’ve survived, and the struggles that shape them. Amal El-Mohtar wrote about birdwatching and the pain of a lost friendship. Mark Oshiro wrote about the incredible motivating power of spite. Maggie Tokuda-Hall wrote about youth activism in the face of censorship.

And then there were those who wrote about what it is to live alongside profound pain. Lucy Bellwood, the artist who created the cover for issue 3, wrote about planting wildflowers in a season of caregiving and grief. Annalee Newitz wrote about espresso and complex loss.

Still others wrote about the expansive world we get to share. Gillian Morshedi wrote about California poppies. Liana Kangas, the artist who created the cover for issue 2, wrote about the thrill of collecting. Jade Song wrote about restlessness, escape, and sending postcards. Premee Mohamed wrote about the sea, and discovering a free and independent life.

There were also essays that dove deep into the soul of being alive. Meg Elison wrote about witnessing and experiencing the kindness of strangers. Bo Bolander wrote about Blind Willie Nelson, who wrote Dark was the Night – a song we sent to space. Peter S. Beagle wrote one of the most beautiful, tender, heartbreaking tributes to lifelong love I have ever witnessed: His reflections on knowing Nell.

And then there were mine. I wrote about a little clay bowl, and changing a tire, and sweeping the kitchen while others are working. I wrote about getting a piercing in a foreign country and holding a small crab. I wrote about hot sauce and eating oysters over the bay.

Those of us who wrote for this project are participating in that enormous, complicated, impossible project. Being alive on purpose. It’s worth it. There is so much life, and so much to live for, and we are so fortunate to get to do it together.

So I'll end the series on this:

Dear Life,

Thank you for everything.

I love you more than anything.

I can't wait to see what's next for us.

- gailey

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive has been a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

I had a wonderful 2025. Yes, the world right outside my door was and still is on fire, with impending horrors always on the horizon. But within my sphere things were good, fantastic even, and I’m very grateful.

I finally saw the Redwoods in Northern California, something I have wanted to see for most of my life. It was an emotional, almost spiritual experience for me, and I absolutely want to go back and see other groves.

I had the surreal experience of standing on a mountain highway on a crisp, clear night, and capturing the Milky Way on my phone. I grew up in a rural area but haven’t been able to see the stars like that since I moved away.

I met beautiful neighborhood cats, ate delicious oysters, and baked my first angel food cake. I made new friends and deepened existing friendships. I injured my knee but brought it back even stronger with physical therapy. I can’t hope that next year will be as good as this one, but I truly appreciated the break in the clouds.

Writing-wise, I had some big accomplishments:

My story “Drosera regina” came out in Lightspeed and was selected by Gizmodo to run on Halloween.

I sold a story to Reactor/Tor.com. “Not Like Other Girls” is slated for Summer 2026.

I sold two other pieces that I can’t talk about yet (paperwork pending), but hopefully can in the spring.

I broke 1k subscribers on this newsletter, thanks to all of you.

I also read a lot of good books this year, mainly literary and horror. I’ve included my favorites below, and I urge you to check them out for yourself or loved ones. Remember, your local public library is always there for you, and you can and should request they order books if they don’t have them. A library purchase is a purchase like any other, and that’s money in authors’ pockets.

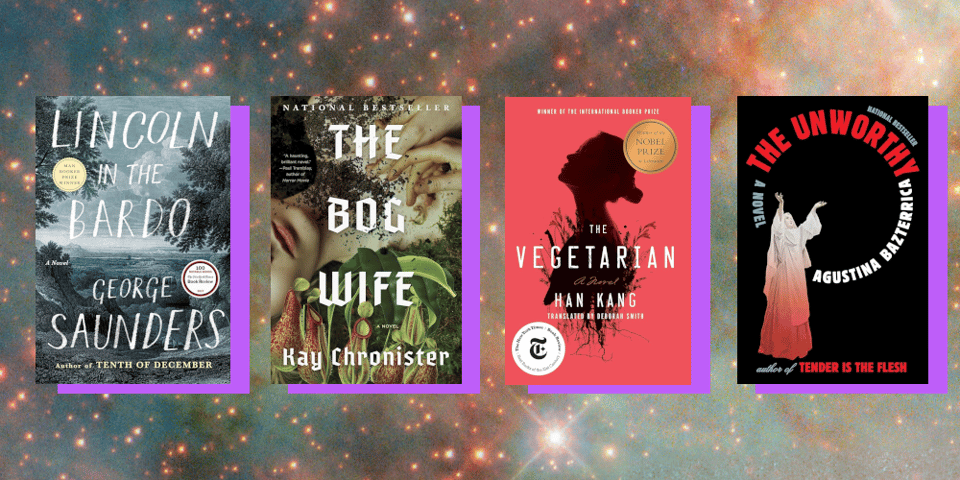

I was crying by page 80, so you know it’s good. Saunders’ highly-anticipated debut novel (after a lauded career in short stories) concerns the real death of Lincoln’s young son, imagining the ghost of the young boy during his first night in the afterlife. It’s a tale of love, folly, and intense grief, and plays to Saunders’ short story strength by unfolding through dialogue vignettes. I will say the ending left me up in the air, but 99% of this book is pure gold.

Part family drama, part modern gothic, part Appalachian folk horror, this book loved to disrupt my expectations. The story of five siblings caring for a rotting manor as they await the arrival of the eldest son’s bog-made wife is really a story about inheritance, love (and its lack), and abuse. It’s a quick read, and I found myself looking forward to it every night the way one does a messy soap opera. The perfect beach read for those who vacation at the swamp.

A story in thirds, each a different viewpoint of someone close to the titular Vegetarian, a woman and wife and sister who stops eating meat after having nightmares. We see the ripple effects through the eyes of her husband, sister, and sister‘s husband, as the Vegetarian is consistently misunderstood and abused. It’s an interesting look at social and gender roles, as well as an exploration of reality and the inevitability of death.

What I like most about this book is its comfort with the strange. Strange things happen, supposed Saints give off unearthly auras, nature comes and goes, and no true explanation is given. Instead we are just covered in heavy atmosphere, religion, and gender. It would be unfair to compare this book to the instant classic Tender Is the Flesh, so I won’t try. But this is a slim, beautiful, climate Gothic with some strange and lasting imagery.

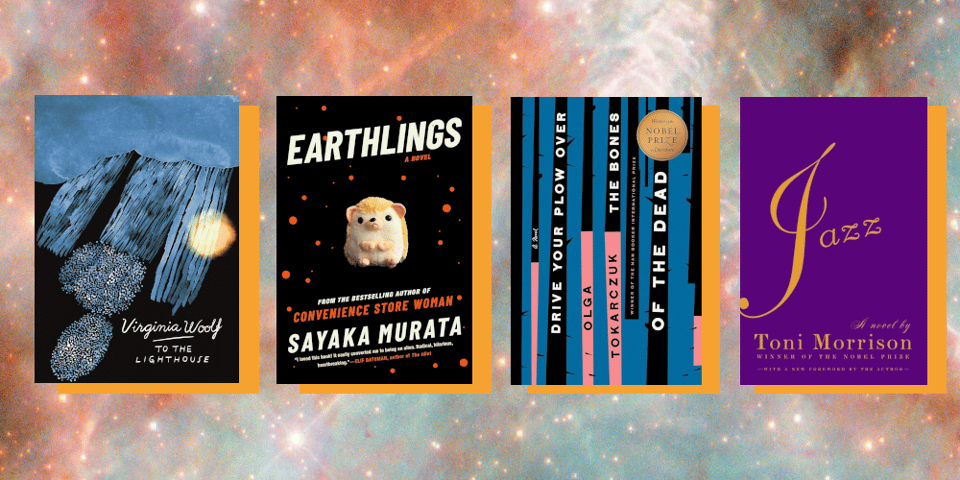

It’s a classic for a reason. A slow, beautiful meditation on life told through the myriad viewpoints of a group of people summering together at the shore. This book is a great example of a novel written before the dominance of film. There are no establishing shots, and the book begins mid-thought inside the mind of a young boy who hates his father. The focalization remains very tight, jumping from person to person, and it took me at least 60 pages to get my bearings. Once everything snapped into place, I loved the trick of it all.

An eleven-year old girl believes she can use magical powers to protect herself. If you read that and thought, “Sounds cute!” this may not be the book for you. If you thought, “Why does an eleven-year old girl need to protect herself?” you’re on the right track. I was told not to do any research before starting this book, and I give you that same advice. But I will also say, this is a very difficult read. It’s certainly Art, in that it made me ask myself challenging questions about my values and the world. But don’t let the cover fool you; this is the darkest book on the list.

An elderly woman with unspecified ailments is caught up in a series of strange murders in her remote Polish village. I have a soft spot for wintertime murder mysteries, and this book is no exception. While certainly a different pace from a traditional detective thriller, this slower, more studious book was a very pleasant and engaging read. I have some quibbles about the book’s structure and execution, but they are not enough to keep me from recommending it. The characters are interesting and the vibe is strong.

Toni Morrison said, “What if I mused poetically about marriage, heritage, and heartbreak, made the winding of time my well-loved jump rope, and dusted each page with sentences sweet as candy?” and I said, “Thank you, Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison.”

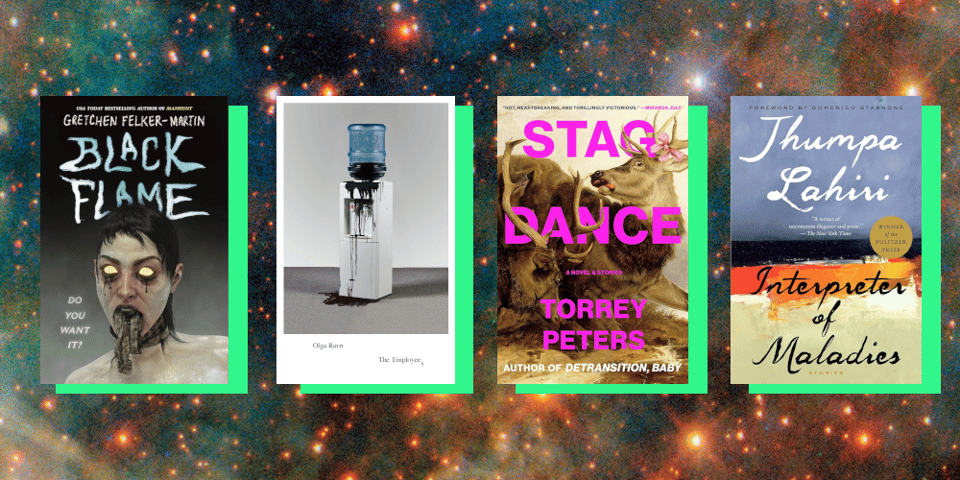

A repressed queer woman must restore an occult film from the 1940s. This book was made to be read one-handed, leaning out a window while smoking a cheap cigarette. It’s pulpy, it’s hot, it’s a love note to classic horror films and queer culture. It’s a fast, sharp read, and a very good (bad) time.

This novella is Type 2 fun, far more pleasurable to remember than experience. A collection of first person reports regarding the arrival of strange objects aboard a spaceship and their impact on the crew, both human and artificial. The brief vignettes cause a disjointed and distanced reading experience that adds up to something similar to the Spoon River Anthology, where the reader has the pleasure of piecing together a larger narrative from multiple viewpoints. My one critique is a section where something is unnecessarily explained, spoiling the subtle and weird vibes. But overall a clever and interesting book.

A collection of four novellas (well, one short novel and three novellas) this book explores the boundary of gender and identity. I liked them all in different ways and different amounts, although my favorite by far is The Chaser, a boarding school romance written with the deft confidence of an author firmly in her wheelhouse with all her tools sharpened. I want a chapbook of it. You should read the collection, but that one most of all.

After coming across Lahiri’s work in The New Yorker, I decided to give her debut (Pulitzer prize winning) collection a read. What an absolute pleasure. She wields straightforward prose to paint deft portraits of characters that seem pressed between the pages. I admire her ability to depict such subtle emotional arcs. I usually list my favorites in a collection, but I liked them all in different ways. Highly recommend this book.

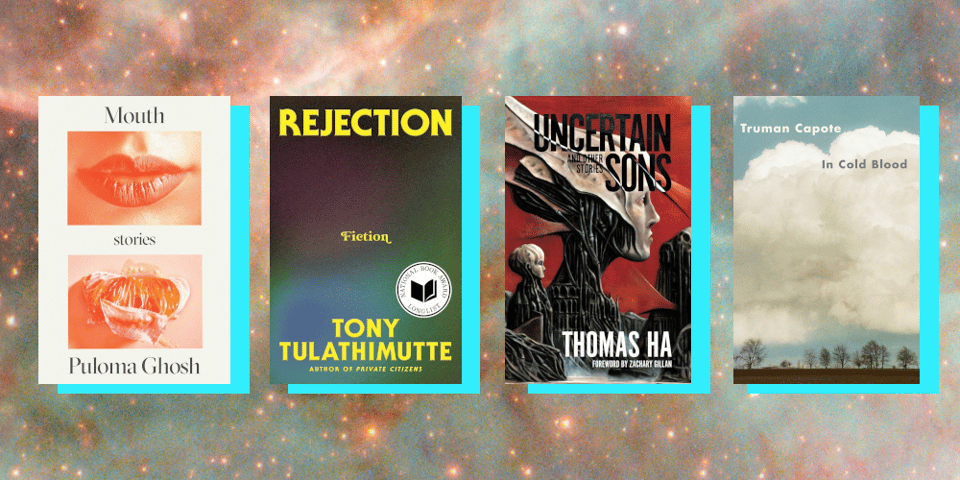

I picked up this collection based on the cover, so hooray for art direction! Ghosh’s debut collection centers around young women, mostly queer, as they wander into dark landscapes and darker relationships. It’s speculative fiction, mainly horror-tinged fantasy, but my favorite stories were the ones more anchored in reality, where Ghosh’s ability to layer on atmosphere and scenery really shine. My favorites include “The Fig Tree,” “Leaving Things,” “K,” “Natalya,” and “Nip,” but you can find sharp lips and slick sex in nearly every selection.

This book is an Internet exorcism. A series of interconnected short stories designed to flush your nervous system with scalding water and purify away all of your worst online neuroses. Tulathimutte paints these portraits of terminally online Millennials so effortlessly that it feels like he copy and pasted something from an Internet forum. It’s the kind of writing where the craft disappears into the truth. Is it a pleasurable read? God, no. But it’s a good one.

Since the arrival of Covid, people have been waiting for The Pandemic Book, a literary work that would perfectly reflect those specific troubled times. My vote is for this story collection, which perfectly encapsulates the past five years of illness, death, political unrest, racism, violence, and climate disaster. Each story is great on its own, but taken together they weave a poignant tapestry of isolation and fear, using devices such as uncanny birds and alien fauna to re-create the emotions of those who lived through that time. I can almost see the historical footnotes in future editions. Favorite stories include “The Sort,” “Window Boy,” and “Sweetbaby,” but they’re all great.

Launching America’s obsession with true crime, this “nonfiction novel” details the events leading up to, during, and after the brutal murder of the Clutter family in November 1959. While Capote flirts with the truth (and one of the killers) on the page to an almost distracting extent, his ability to weave a narrative and pen beautifully sharp prose makes for a captivating read. I couldn’t put it down.

“Manifest” by ‘Pemi Aguda. A young woman is accused of harboring a malevolent spirit. Is it magic? Or plausible deniability? Aguda’s debut collection Ghost Roots came out last year.

“In Connorville” by Kathleen Jennings. Sisters share fantastical stories about the people in their hometown. Jennings’s latest book Honeyeater came out this year.

“Pearlescent Tickwad” by Samir Sirk Morató. A woman discovers she’s made of millions of ticks. Can she ever be a good mother? Morató’s debut collection Gore Poetics comes out in 2026.

Has this list inspired you to read more in 2026? Well, now is the time to start! Don’t fret about setting goals or comparing yourself to others. I don’t try to read a specific number of books each year. I just read.

Get a library card. Your library is an indispensable public service, offering everything from physical books to ebooks to movie streaming and video games.

Download Libby or Overdrive or an e-reader app to your phone. Don’t doomscroll. Read a book instead.

Subscribe to short fiction magazines. Short fiction is greatly undervalued, meaning you can get a lot for very little money. Most will send you ebooks, and some still do physical copies.

Happy New Year!

The thirty-first quatrain in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues the existentialist theme of the unknowable character of our fates and of our deaths. That is, the underlying Persian poetry as well as FitzGerald’s mid-Victorian rendering questions whether it all has a purpose.

XXXI.

Up from Earth’s Centre through the Seventh Gate

I rose, and on the Throne of Saturn sate,

And many Knots unravel’d by the Road;

But not the Knot of Human Death and Fate.

A. J. Arberry identified the original here as no. 319 in the Calcutta Manuscript, which can also be found here on the Web.

از جر حضيض خاک تا اوج زحل

کردم همه مشکلاتِ گردون را حل

بیرون جستم ز بند هر مکر و حَیَل

هر بند گشاده شد مگر بند اَجل

Here is my rendering of this quatrain in blank verse:

From earth’s dark depths to Saturn’s pinnacle

I solved the puzzles of the turning skies.

I slipped the bonds of every trick and sham;

Each shackle was removed except for death.

As can be seen, FitzGerald’s translation is fairly close to the original. One difference is that he translated band which has connotations of “bond” or being tied up, as “knot.” Since unraveling a knot suggests solving a puzzle, the East Anglian poet shifted the meaning of this stanza from being unable to escape death to being unable to understand it. Since the second hemistich actually does talk about solving the difficulties of the heavenly vault, however, FitzGerald’s interpretation is reasonable. Death is the one difficulty that the polymath of the poem cannot resolve — can neither escape nor fathom.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The mention of Saturn and the vault of heaven plays to the literary fiction that this poetry was written by an astronomer at the Seljuk court, Omar Khayyam (d. 1131). Khayyam was in fact a frame author, to whom unconventional, heterodox and libertine poetry by various hands was attributed. He functions as Scheherazade does for the 1,001 Nights; stories told in Cairo or Aleppo or Baghdad over the centuries were all attributed to her.

Bowl with Courtly and Astrological Motifs, late 12th–early 13th century, Central or Northern Iran. The figures and decoration on the interior of this bowl combine imagery of the courtly cycle and astronomy. In the center the sun is surrounded by personifications of the planets (clockwise) Mars, Mercury, Venus, the moon, Saturn, and Jupiter. Islamic astronomers believed the planets orbited the earth, forming seven concentric circles. An eighth, outer sphere contained the constellations and signs of the zodiac, possibly represented by the six large and twelve small gold circles between the planets’ heads. Public Domain. Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

Our inability to understand or reckon with death is a common theme in classical Persian poetry.

Take this passage from a ghazal or ode of Hafez of Shiraz (d. 1391):

مرا از ازل عشق شد سرنوشت

قضای نوشته نشاید سترد

مزن دم ز حکمت که در وقت مرگ

ارسطو دهد جان، چو بیچاره کرد

I would translate this as an alexandrine, this way:

From pre-eternity my fate was ardent love;

Once written in the stars, your fate cannot be changed.

Do not bring up philosophy, since when death comes

great Aristotle breathes his last, just like the poor.

As with the Omarian poetry that FitzGerald translated, so here Hafez insists that however clever someone may be, however many of life’s puzzles they may have solved, when death comes it takes that philosopher or scientist no less inscrutably and inexorably than it does a poor person on the street.

Aristotle was perhaps the most influential philosopher in medieval Islamic thought, though Neoplatonism was also extremely popular.

—-

For the previous quatrain, see “Another Cup to Drown the Memory:” FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:30 .

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

Apollo 13 is a film that sits atop a small but diverse and, for some people, extremely enjoyable sub-genre of film: Competence Porn. This has nothing to do with actual pornography (well, I guess it could, given the right pornographic film, but I am not aware of one, nor am I going to stop writing to find out) and everything to do with competence: exceptionally smart and capable people doing exceptionally smart and capable things in moments of crisis where the alternative to being competent is, simply, disaster. There are other very good movies in this genre — The Martian is a favorite of mine, and rather more recent than this film — but the added edge that Apollo 13 has over so many other of its competence porn siblings is this: It really happened.

And, to a degree that is unusual for Hollywood, the real disaster and journey of Apollo 13 happened very much like it happens in this movie. There is a missed telemetry burn here and a scripted argument there (and a few other minor things) to separate the two, and Tom Hanks doesn’t really look much like Jim Lovell, the astronaut he portrays. But in terms of film fidelity to actual events, this is about as good as it gets. With an event like this, you don’t need too much extra drama.

The event in question is a big one: On the way to the moon in April 1970, the Apollo 13 mission experienced a major mishap, an oxygen tank explosion that threatened the lives of the crew members, Jim Lovell (Hanks), Fred Haise (Bill Paxton) and Jack Sweigert (Kevin Bacon), and would prevent the Apollo 13 crew from touching down on the moon. The three astronauts and the entire mission control crew back in Houston, led by Gene Krantz (Ed Harris) and bolstered by astronaut Ken Mattingly (Gary Sinese), improvised a whole new mission to get the Apollo 13 crew back home, alive.

On one hand, there is irony in declaring this film to be about extreme competence when it is about a technical incident that jeopardized three lives, and, had the rescue attempt ended tragically, could have curtailed the entire Apollo program after only two moon landings. But on the other hand, there is the competence involved in getting things right, which while ideal, doesn’t offer much in the way of drama, and then there is competence involved in saving the day when things go south, which is inherently more dramatic. I’m sure if you were to have asked Lovell, commander of the mission, he would have told you that he’d prefer that everything had gone according to plan, because then he would have landed on the moon. But after that explosion, he probably appreciated that everyone in Houston turned out to have the “Improvise, Adapt, Overcome” type of competence as well.

This sort of competence happens several times in the film, but the scene for me that brings it home is the one where carbon dioxide levels start to rise in the lunar lander module, and the crew in Houston has to adapt the incompatible air scrubbers of the command module to work in the lander — literally putting a square filter into a round hole. This is possibly the most unsexy task anyone on any lunar mission has ever been tasked with, given to (we are led to believe) the people at NASA not already busy saving the lives of the Apollo 13 astronauts. Unsexy, but absolutely critical. How it gets done, and how the urgency of it getting done, is communicated in the film, should be studied in cinema classes. Never has air scrubbing been so dramatically, and effectively, portrayed.

This brings up the other sort competence going on in this film, aside from what is happening onscreen. It’s the competence of Ron Howard, who directed Apollo 13. Howard will never be seen as one of the great film stylists, either in his generation of filmmakers or any other, but goddamn if he’s not one of the most reliably competent filmmakers to ever shoot a movie. Howard’s not a genius, he’s a craftsman; he knows every tool in his toolbox and how the use it for maximum effectiveness (plus, as a former actor himself, he’s pretty decent with the humans in his movies, which is more than can be said for other technically adept directors). Marry an extremely competent director to a film valorizing extreme competence? It’s a match made in heaven, or trans-lunar space, which in this case is close enough.

Howard and his crew, like the Apollo 13 mission control crew, also had the “Improvise, Adapt, Overcome” point of view when it came to how to solve some of its own technical problems, such as, well, showing the flight crew of Apollo 13 in zero gravity (yes, I know, technically microgravity, shut it, nerd). This film was being shot in the first half of the 1990s, when CGI was not yet up to the task of whole body replacement, and most practical solutions would look fake as hell, which would not do for a prestige film such as this one.

So, fine. If Howard and his crew couldn’t convincingly fake zero gravity, they would just use actual microgravity, by borrowing the “Vomit Comet,” the Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker NASA used to train their astronauts. It very steeply dives from 38,000 feet to 15,000 feet, giving everyone inside the experience of weightlessness for 23 seconds or so each dive. Howard shoved his Apollo 13 spacecraft sets into the plane and rode up and down and up and down and up and down, filming on the dips, until the movie had all the zero-gravity scenes it needed. Then the actors had to go back and re-record all their dialogue for those scenes, because it turns out filming on a vomit comet is a very loud experience.

I think this all very cool and also I am deeply happy I was not on that crew, because I would have never stopped horking. I believe every member of the cast and crew who were on that plane should be known as honorary steely-eyed missile people.

Apollo 13 is, to my mind, the best film Ron Howard has yet made, the one that is the best marriage of his talents to his material. Howard was, frankly, robbed at the Oscars that year, when the Academy chose Braveheart over this film and Mel Gibson as director over Howard. These were choices that felt iffy then and feel even more so now. Howard would get his directing Oscar a few years later with A Beautiful Mind (plus another one for producing the film with Brian Glazer). That film was an easy pick out of the nominees that year — 2001 was not an especially vintage year in the Best Picture category, which helped — and also I feel pretty confident that the “Al Pacino factor” (i.e., the award given because the award should have been given well before then) was also in play. An Oscar is an Oscar is an Oscar, especially when you get two, so I’m sure at this point Howard doesn’t care. He did get a DGA Award for Apollo 13, so that’s nice.

I haven’t really talked much about the cast in this film, except to note who plays what. That’s because, while everyone in this film is uniformly excellent, competence requires everyone on screen to mostly just buckle down and do the job in front of them. With the exception of one argument up in space, no one from NASA gets too bent out of shape (and tellingly, the argument in the film didn’t happen in real life because astronauts just do not lose their shit, or at least, not in space). This works in the moment, and Howard and his team do a lot of editing and music and tracking shots and such to amp it all up, but it doesn’t translate into scene-chewing drama. This film lacks a Best Actor nomination for Tom Hanks, which might have hurt its chances for Best Picture. Its acting nominations are in the supporting categories, and it’s true enough that Kathleen Quinlan, as Jim Lovell’s wife Marilyn, gets to have a wider range of emotions than just about anyone else (Ed Harris was also nominated; his performance is stoic as fuck).

(To be fair, Hanks was coming off back-to-back Best Actor wins. It’s possible Academy members were just “let someone else have a turn, Tom.”)

Every film ages, but it seems to me that 30 years on, Apollo 13 has aged rather less than other films of its time (and yes, I am looking at you, Braveheart). Again, I think that this comes down to competence, on screen, and off of it. The story of hard-working people saving the day ages well, and Howard’s choices (like the actual microgravity) mean that the technical aspects of the film don’t give away it’s age like they otherwise might.

The thing that ages this film most, alas, is nothing it has anything to do with: the recent decline in the application and admiration of competence, in many categories, but in science most of all. Watching Apollo 13, one acknowledges that those were indeed the good old days for competence. Hopefully, sooner than later, those days will return.

— JS

Only the misfortune of exile can provide the in-depth understanding and the overview into the realities of the world. — Stefan Zweig

Newark, Delaware (Special to Informed Comment; Feature) – In the last few decades, Iranian cinema has gained a prominent status in the world of cinema, winning many prizes including the Oscars, the Cannes film festival, the Venice film festival and other European awards.

When one looks at the history of cinema in Iran, a few names are on top of the list: Dariyoush Mehrjoui, Abbas Kiarostami and Bahram Beyzai. Dariyoush Mehrjoui and his wife were murdered at their home outside of Tehran. To this day, no one knows who the real culprit was. Kiarostami stayed in Iran but was constantly under pressure and censorship. He died in a hospital in Paris.

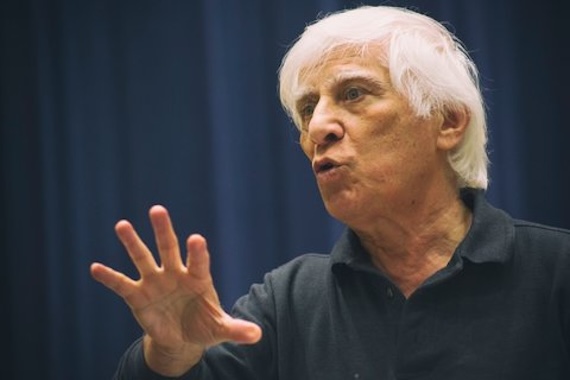

Bahram Beyzai (1938-2025), who had the title of ustad, master, left Iran as his films were being targeted by the Islamic Republic which has censored and imprisoned many artists, including filmmakers.

Bahram Beyzai became famous with his heart-wrenching film, “Bashu, the little Stranger” (1986), which depicts life in rural Iran, in Gilan, a province in northern Iran.

He was a pioneer and a leader of the new age cinema of Iran.

Born into a family of poets who were Bahais, his father had composed several poems. Always interested in movies, at a very young age, he started to write screen plays and was one of the founders of the Iranian Writers’ Guild.

Beyzai became a mentor to many upcoming artists teaching at Tehran University until 1979.

He was ousted from the University in 1981 during the infamous cultural revolution.

Beyzai left Iran in 1995 for a film debut in Strasbourg, France but returned to write more screenplays.

After much struggle with censorship and pressure, he finally left Iran in 2010 and settled in Northern California where he continued his work, even though his heart was always in Iran. Since then, he taught at Stanford University’s Iranian Studies center. He was not just a director but a filmmaker and a playwright.

Bahram Beyzai, “Bashu, the Little Stranger”

[This post contains video, click to play]

Far away from home, he worked hard to renew his once thriving profession. He taught various film classes at Stanford.

He also gave lectures and sought to regain his identity as a famous filmmaker. But he remained chagrined, not to have been able to go back to the country he dearly loved and identified with.

Following his death, the torrent of messages of sadness and comments on social media from all over the world showed that he had never lost his allure.